Dr Juhi Tandon explains why GPs must embrace online healthcare to deliver the best care to patients with limited English proficiency.

GP practices are under pressure. Viruses, such as COVID-19 and flu, will add to the burden this winter. This is also at a time when GP numbers are declining due to burnout, and less doctors are choosing to go into the general practice.

Currently, around half of GP appointments are taken up by patients with long-term conditions that can be managed, but not treated.[1] These long-term conditions are twice as common in adults from poorer backgrounds – many of whom face language barriers.[2] Such evident health inequality can only be expected to increase given that Coffey has recently scrapped the health inequalities paper that was meant to be published this year.[3]

Around 10% of the UK population speaks English as a second language, with 1.3% (726,000) citing that they don’t speak English well. [4] This language barrier means that these patients may struggle to access health services or adequately manage their health at home or struggle to follow the medical advice given to them.

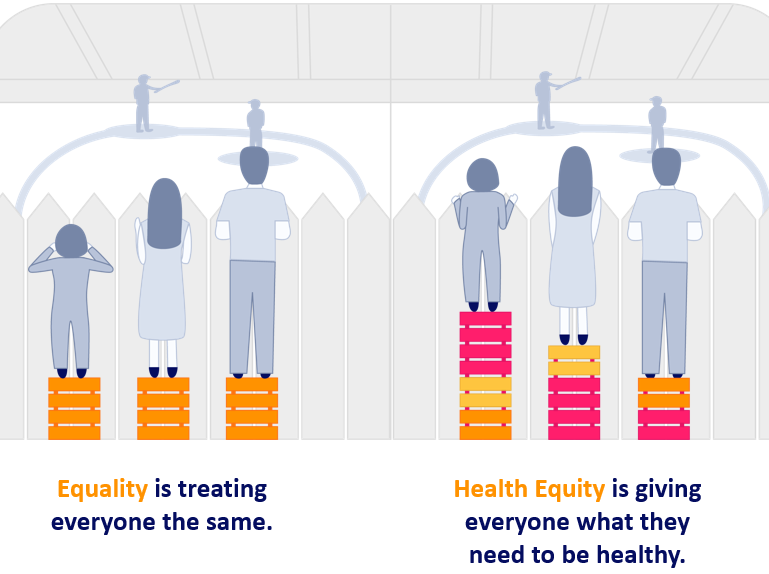

How do we achieve health equity?

To achieve health equity, it’s not enough to provide the same services to everyone. You need to tailor services to what patients need.

While the NHS does provide a means of offering health information in different languages, one of the key issues is that the advice is not culturally resonant. To give one example, I remember advising an Eritrean lady on managing her hypertension. The information leaflet I gave her was focused on diet advice for a western person. This information clearly didn’t resonate with her on a cultural level because she wasn’t used to the foods mentioned on the leaflet. As a result, she maintained the same diet she’d had for fifty years – at a cost to her health.

Face-to-face consultations with patients who struggle with English can also lead to sub-standard care. Language Line is a great service but as GPs, we don’t have time in a 10-minute appointment to call the line, be put on hold, wait for the right person, speak to a third person and then translate the entire consultation.

One way of overcoming this is to book a double appointment with a translator, but a GP is often already locked in to a ten-minute appointment by the time they realise a patient is struggling to communicate. The pressure on availability also means double appointments are not being offered even when they’re needed due to lack of capacity or workforce shortages.

With appointments in short supply, it’s no surprise that patient gets fed up if they’re told to come back later. This leaves patients disengaged with care services and frustrated with clinicians, making it difficult for the necessary trust to be built between them so their health can be improved.

Sometimes patients come in with a family member who then acts as the translator, but this also has problems. A 55-year-old Bengali lady may be too embarrassed talk about her urinary tract infection with her son translating. With some health conditions, family translators can lead to ethical conflicts and legal issues.

Accessible health information will help to solve the issue

At one practice where I worked, we served a large Bengali population with high rates of uncontrolled diabetes and hypertension. To solve this challenge, our practice had a doctor-led weekly three-hour Bengali clinic with 30 to 40-minute appointments and a translator. The standard of care was fantastic. Our Bengali patients felt more involved, listened to and were more actively engaged with their health. As a result, treatment adherence improved which benefited management of their long-term conditions, and overall outcomes.

Many GP practices, however, can’t afford to hire an extra doctor and a translator to run a specialist clinic. Investment in care also requires leadership and clear standards for delivery, but this isn’t always happening. One hope I had in Coffey’s health inequalities paper was to tackle the shortage of GPs in poorer areas to help with problems such as these.

Health information providers are often scared of getting a translation wrong and injuring a patient and sadly, the new NHS accessible information standard gives little guidance on the right way to translate. [5] This is surely a patient safety issue, and it should be treated as such. Until patient experience is given the same targets and standards as patient safety, it is going to be very difficult for trusts, however willing, to focus on it, and improve health equity. So, what is the solution, while we operate with limited resources to improve patient experience?

How digital can bridge the language barrier divide

My experience of remote consultation is that it can help to reduce health inequality by making services more accessible. Those with mental health or mobility issues, who would have struggled pre-pandemic to attend the surgery, can now have an appointment without leaving home.

There is an opportunity to work in partnership with patients with long-term conditions to develop online educational resources – bringing health information to life through 360-degree video and animated digital tools. Here, we are using digital health information to build trust with patients and relieve pressure on GPs.

Cognitant’s chronic kidney disease tool, for example, uses infographics to explain the link between hypertension, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. Each tool is not only translated, but also placed in a cultural context.

It’s so important to provide the right information to patients, regardless of English proficiency. Only 50% of information is retained by a patient in a GP appointment, and this falls to less than 20% after seven days. By using visual, interactive education resources which patients can access after an appointment (and visit repeatedly) we can make sure people understand health information in a way that makes sense to them.

Patient trust is key

Building trust with patients and ensuring health information is easily available is essential to improving treatment compliance and health outcomes. Once people understand their health, they can better manage their condition.

By giving everyone powerful tools to manage their own health, we can place everyone on an equal footing and deliver true health equity but we need to address this now before it’s too late.

Juhi Tandon

Dr Juhi Tandon, is a practicing GP in Buckinghamshire and Medical Director at Cognitant.

References

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/health-and-social-care-secretary-speech-on-health-reform

[2] https://www.bma.org.uk/media/2084/health-at-a-price-2017.pdf

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2022/sep/29/therese-coffey-scraps-promised-paper-on-health-inequality

[4] https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/demographics/english-language-skills/latest

[5] https://www.england.nhs.uk/about/equality/equality-hub/patient-equalities-programme/equality-frameworks-and-information-standards/accessibleinfo/

Cognitant

Looking to empower people with health information for better patient outcomes?

Related News

Kidney Research UK invests in Healthinote patient education platform which could support >15m people with long term health conditions

April, 2025

Oxford, January 2025 – Kidney Research UK, the leading charity dedicated to kidney health, has made a significant investment in Cognitant Group Ltd, a leading...

Webinar Insights – Compliance vs Patient Engagement: Can They Co-Exist?

April, 2025

Is compliance really a barrier to meaningful patient engagement in pharma, or are outdated myths holding us back? In this recent webinar, Dr Tim Ringrose,...

Funding awarded to innovations that support early diagnosis and rehabilitation of Stroke patients

March, 2025

SBRI Healthcare, an Accelerated Access Collaborative (AAC) initiative, in partnership with the Health Innovation Network, has awarded £2.5 million for the development of five innovations...